Two monks steal into a darkened room under the cover of night. The younger of the two raises a lantern over his head, the flickering flame revealing the scriptorium. This is a place the monks know well — it’s where they work their days away copying manuscripts by candlelight.

The elder monk guides the younger to one of the desks, where a book has been left open.

“Here it is,” he says, suppressing a giggle.

“Here is what, Master?” asks the younger monk.

“Be silent, boy, and listen,” he whispers sternly. His eyes return to the page in front of him. “And move the light closer.”

The young monk obliges, and the old monk begins to read aloud:

“I go forward with my nose to the ground, brought from the wood, bound by skill, carried on wheel. I have many marvels: as I go, one side is green; and my path is clear, black on the other side.”

The old monk pauses, a mischievous smile playing on his lips, "What am I?"

The novice furrows his brow, pondering what the words might mean — but, alas, he isn’t yet clever enough to answer the book’s riddle.

Are you?

The thousand-year-old book of mysteries

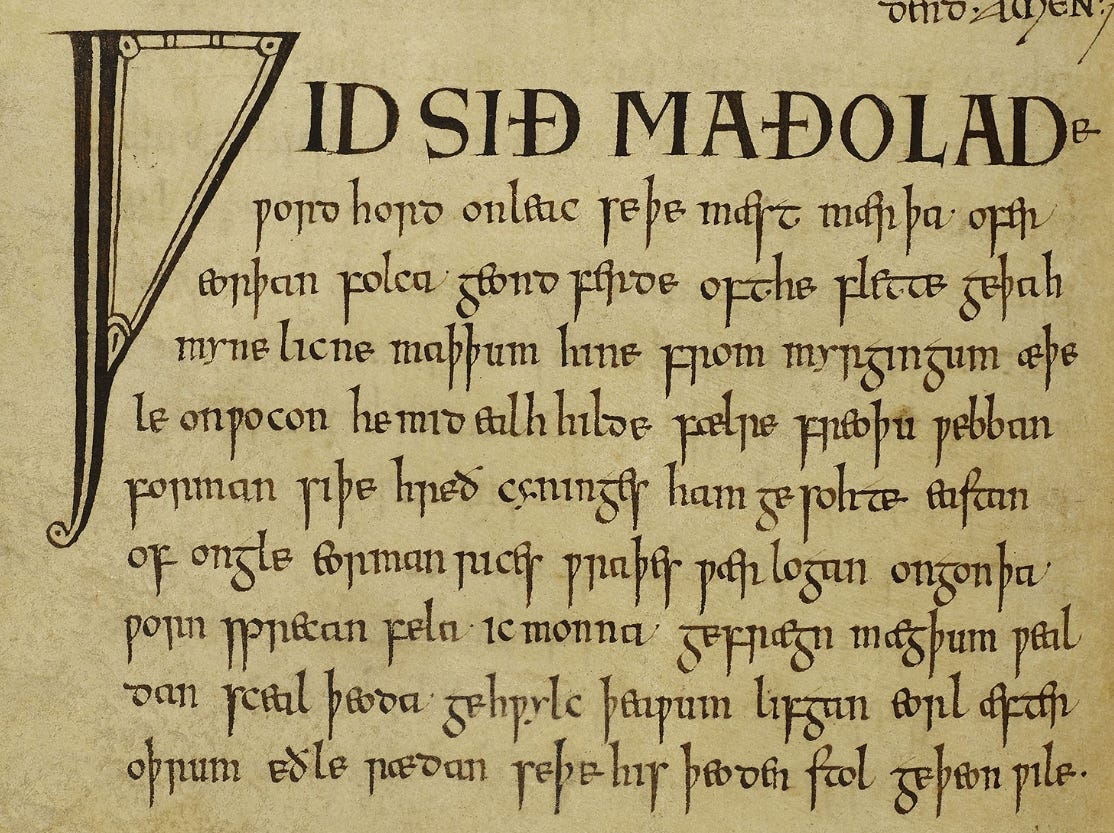

In a cathedral library in southwest England rests one of the most remarkable literary treasures of the medieval world — the Exeter Book. This manuscript, which was compiled around the end of the tenth century AD, contains a sixth of all surviving Old English poetry, including nearly a hundred riddles that have confounded readers for centuries.

The riddles of the Exeter Book are not the only riddles to come out of early medieval England. There are others, for example, written in Latin. But the Exeter Book riddles are the most famous — probably because they’re written in English. More specifically, they’re written in Old English, the early form of the English language spoken from roughly AD 450–1100.

Unlike their Latin counterparts, which helpfully provided solutions, the Exeter Book riddles come to us without answers. This leaves ample room for interpretation among scholars and casual readers alike, especially because some of the riddles are much harder to work out than others!

Here’s another one, Exeter Book Riddle 18:

I am a marvellous thing. I cannot speak a word,

nor talk with people, although I have a mouth,

and a big belly.

I was on a boat with more of my kind.

Any guesses? Most people think the answer to this riddle is probably a jug of some kind. But we don’t know for sure, since the authors didn’t leave us the answer key.

What is most interesting about these riddles is how sophisticated they can be — they are, in fact, poems, which use metaphor, personification, and vivid imagery to transform the ordinary world into something strange and magical: a shield becomes a warrior speaking of its battle scars, an onion tells of making men weep, a storm describes its journey across the sky.

Objects that speak

What makes these riddles remarkable is their ability to bring ordinary objects and creatures to life through metaphor. In Riddle 14, a horn describes its former life as a “weaponed warrior” that now “swallows breath” and “puts enemies to flight with its voice.”

Riddle 26 brings to life the process of creating a Bible, describing how “a certain enemy took away my life” when the animal was killed for parchment, then “he soaked me, dunked me in water,” before finally being transformed when “he clothed me with protective boards.”

And in Riddle 7, we read, “My garment is silent when I tread the earth, or dwell in the towns, or stir the waters. But sometimes my trappings and this high air lift me over the habitations of heroes, and then my robe sings loudly” — this probably describes a swan.

When Anglo-Saxons began riddling, they entered a realm where objects and animals possessed agency and voices of their own, and where the boundaries between the animate and inanimate were fluid and porous.

Like much of Old English literature, the Exeter Book’s riddles have a dual heritage. On one side, they show clear influence from the Latin riddles brought by Christian missionaries. Two of the Exeter Book riddles are, in fact, translations of Latin riddles written by an Anglo-Saxon bishop named Aldhelm.

But they also draw upon older, oral practices — a perfect example of which can be seen in the riddles’ poetic form. The Exeter Book riddles are written using the same poetic rules as almost all other Old English poems: alliterative verse. The result is something unique — something that could only have come about in early medieval England.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the Exeter Book riddles is their occasional bawdy humour. Several riddles employ clever double entendres that seem innocent on the surface but provide ample opportunity for baser interpretations. Riddle 25 describes something that “stands hard in the bed” and is “a joy to women” (the answer is an onion — what were you thinking?).

Windows into history

Beyond their literary merit, these riddles offer us a window into early English life — one unlike any offered by other texts from the period. They describe everyday objects, animals, weather, and tools with intimate familiarity.

The frequent references to weapons, shields, and battle suggest a society well-acquainted with warfare — no surprise to students of medieval history, of course. But riddles about ploughs, bread-making, and leather-working reveal the practical foundations of daily life. Descriptions of storms and natural forces display the awareness of the power and capriciousness of nature that every agricultural society has keenly felt.

But what's absent is equally revealing. Unlike other Anglo-Saxon poetry, with its focus on heroic values like praise and glory, the Exeter Book riddles rarely dwell on abstractions like love, death, good, and evil. Instead, they stay firmly planted in the tangible world — they’re concerned mostly with the material reality around them.

Why riddles still matter

From Oedipus and the Sphinx to Gollum and Bilbo Baggins, stories of riddles still delight us today. But the Exeter Book riddles in particular seem to appeal to our modern sensibilities. Their lack of definitive solutions evokes our modern appreciation for ambiguity and multiple interpretations. The way they use metaphor to de-familiarize everyday things feels remarkably like modern poetry's attempt to make the ordinary strange again.

The next time you're caught in a downpour or warming your hands by a fire, consider how an Anglo-Saxon riddler might have described these experiences — giving voice to the elements themselves. In doing so, you'll be participating in a tradition that has transformed the ordinary into the extraordinary for over a thousand years, playing what scholar Craig Williamson called an “ageless game,” one which lets us see the world anew.

P.S. Have you guessed the answer to the monk’s riddle? This is a part of Riddle 21 in the Exeter Book. The answer is usually understood as the plough, which takes a green field and turns it black as it churns the soil.

Yes, I knew it was probably a plough because I studied quite a bit of Anglo Saxon poetry when doing my MA. I love the Exeter Book riddles particularly.

We know that riddling was a common pastime of the Vikings who would compete in a battle of words when in company.

I think these riddles (in spoken form) have been passed down to us from well before the Anglo Saxon period.

I so enjoyed this article...looking forward to more.

Thank you